Nature needs YOUR land ethic!

Stay connected through our down-to-earth e-news.

Principles in this story: Economics in Conservation, Ecosystem Integrity, & Leadership in Conservation

Photo credit: Jim Brandenburg

Many conservationists today are as concerned with the health and well-being of humans as they are with protecting and fostering nature.

To tackle these interconnected goals, conservationists take a wide variety of actions, including building awareness of the threats facing protected areas, engaging with local communities, and advocating for policy changes.

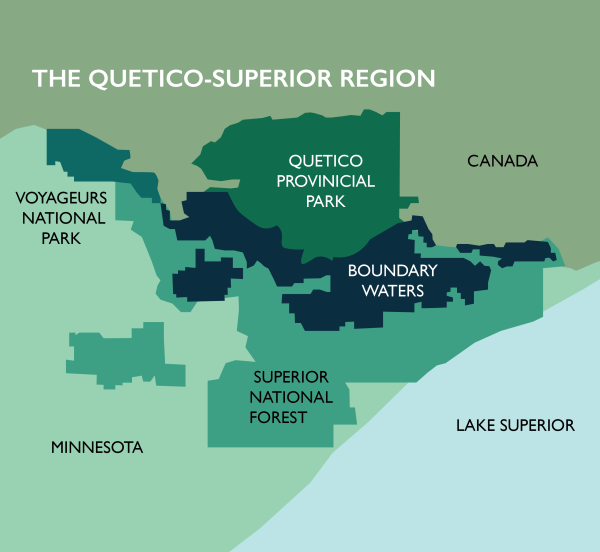

In this story, we feature three leaders who dedicate time to protecting the most visited wilderness in the U.S.: The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW). The BWCAW comprises over one million acres of pristine forests, glacial lakes, and streams within the Superior National Forest in northeastern Minnesota.

These leaders’ advocacy and engagement efforts are creating positive ripple effects and influence far beyond the BWCAW. Read on to learn more.

Duluth, Minnesota – With bravery, strength and passion, Emily Ford pushes herself to new heights, and in doing so, draws attention to wild places.

“I’m not super vocal about how I feel, my stance on things, but if I can show you what we’re protecting, I’m hoping people will be like, wow, this is a place that only exists if we protect it,” says Ford, the subject of a documentary, A Voice for the Wild

For a month during winter of 2023, Ford lived in the BWCAW where she skijored with sled dog, Diggins, facing subzero temperatures and miles of solitude to raise awareness of the threats to the watershed and to raise money for Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness, which gives young people the opportunity to experience the outdoors.

For decades, mining companies and environmental groups have been embroiled in disputes over efforts to keep threats to the watery wilderness at bay. At the center of the debate is whether or not sulfide-ore mines for copper and nickel be built adjacent to and upstream of the BWCAW which is in the Superior National Forest.

Environmental groups against sulfide-ore mining — novel in Minnesota — argue that the industry would impact the water quality of the more than 2,000 lakes in the area along the U.S.-Canada border. The metals from such a mine are used in a host of everyday items including electrical and electronic products and in stainless-steel production.

“We as humans need these resources, right, but we don’t always know the implications of what we are doing when we are gathering resources from the Earth,” says Ford in the film.

Last summer, Ford took some time away from her head gardener job at Glensheen Mansion to sit down with the Aldo Leopold Foundation. She readily shared her trail tales and her journey to falling in love with the wild.

In addition to protecting wild places, Ford is also an advocate for increasing accessibility to outdoor recreation — including for people of color and those who have been historically marginalized — to help close the nature gap. Of hiking trails and the wilderness, Ford wants people of color to know, “It’s for you. It’s for me. This is your space. This is your home also.”

In the seventh grade, young Becky Rom led her first campaign to protect the Boundary Waters. Born and raised in Ely, Minnesota, Rom knows how public land and private interests can marry. Rom is the daughter of a local outfitter, Bill Rom, who advocated for decades, from the 1940s through the 1960s, for the protection of the Minnesota-Ontario border region and the Quetico-Superior wilderness area.

Rom continues the charge today and is leading the fight for unspoiled wilderness, clean water, and a sustainable local economy. Rom is the national chair of Save the Boundary Waters, based in Ely, which has formed coalitions with hundreds of national organizations and local businesses.

Formerly a partner at a law firm, Rom draws on legal rights, history, and science to build public and political support. Her aim, as she wrote in a recent opinion piece for the MinnPost, is clear:

“Thwarting the pillaging of our wild public lands for private gain.”

Save the Boundary Waters is calling for a permanent ban on sulfide-ore mining in the Boundary Waters watershed. The group cites peer-reviewed research showing that the mining would threaten water quality, wildlife, human health, and the region’s ability to sequester carbon—an especially critical function, as the area’s boreal forests store more carbon than any other terrestrial ecosystem.

In 2020, an independent study by prominent Harvard economist James Stock, former chair of Harvard’s economics department and former member of the White House Council of Economic Advisors, compared the economic impacts of the Forest Service’s then proposed 20-year mining ban near the Boundary Waters with the potential consequences of sulfide-ore copper mining in the watershed.

The conclusion: more jobs and more income in the region are generated by protecting public lands near the Boundary Waters than by sulfide-ore copper mining.

Wilderness-edge communities like Ely have a big role to play in protecting wild places. According to Rom, Ely thrives because of its proximity to the wilderness and its location in the Superior National Forest.

“There is always a push and pull between economic development and wilderness preservation, and communities are often divided as a result,” says Rom. “Our role is to try to unite the community and celebrate public lands and acknowledge what they bring to the community, which is economic, but it’s far beyond economics. And the reason why we have new residents is because people want to live next to the world’s greatest canoe wilderness.”

Thea Sheldon dreamed of moving to Ely, Minnesota all of her life. In retirement, Sheldon and her husband did just that. After fulfilling that dream, Sheldon joined other residents in taking on a challenge that requires ongoing community conversation and shared action. As numerous organizations have pointed out, “Ely is a small town with a big wildfire risk problem.”

The town of Ely is physically located in the heart of the Superior National Forest and residents, government agencies, and community-based organizations are addressing the high risk of catastrophic wildfire in northeastern Minnesota while sharing knowledge about fire’s ecological benefits. In doing so, community members are working to balance the need for fire to restore the land with the need to ensure community safety.

Now neighbors in Ely are coming together to act collectively and prevent harm to structures from unplanned fires. “We realized that our properties were only as safe as the neighbor’s property,” says Sheldon.

Sheldon adds, “It isn’t just about structures though, it’s also about the health of the forest. Actually, our Boreal Forest is fire dependent, it needs fire in order to regenerate, to regenerate the trees.”

With such dynamic factors associated with a municipality of more than 3,000 people essentially living in a public National Forest, social relationships, trust, and cooperation are essential. To help foster community dialogue and relationship building, Save the Boundary Waters started Boundary Waters Connect, a weekly meeting group in which residents learn together, connect, and welcome newcomers.

In 2024, representatives with the Aldo Leopold Foundation experienced Ely’s welcoming ways firsthand when we collaborated with the U.S. Forest Service to bring together residents and issue-experts for “A Celebration of the Land Ethic and Conservation Symposium.” In the words of Buddy Huffaker, Executive Director of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, “Ely was chosen as a community that is working through conflict toward conservation solutions that promote and protect ecosystem integrity, human health and well-being, and cultural vitality.”

Sheldon is proud of the growing momentum in Ely.

“People are raising their hands, and saying, ‘I want in!’”

The three leaders featured in this story represent different pathways to building awareness and better understanding of and appreciation for the complexity of the issues we face as a society.

Aldo Leopold often talked about “public interest in private land,” and in northeastern Minnesota, the intersection of public and private land issues demonstrates numerous critical challenges, such as resource management and environmental protection.

This story includes commonly used jargon in conservation. To explore more, click on a concept below which will take you to the Jargon Buster Tool for an explanation and additional examples.

By sharing these stories, you help advance Aldo Leopold's Land Ethic, fostering awareness, inspiring stewardship, and strengthening the collective impact of conservation.

Carrie Carroll is the land ethic manager for the Aldo Leopold Foundation. Carrie is working to share stories about meaningful relationships between humans and public and private land to inspire greater action in conservation.

The Aldo Leopold Foundation was founded in 1982 with a mission to foster the Land Ethic® through the legacy of Aldo Leopold, awakening an ecological conscience in people throughout the world.

"Land Ethic®" is a registered service mark of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, to protect against egregious and/or profane use.

Stay connected through our down-to-earth e-news.